The Omicron wave appears to have peaked in some countries, with the UK preparing to loosen restrictions. Mark Ainsworth, Head of the Schroders Data Insights Unit, explains what to expect next.

The Omicron variant has spread rapidly since its initial detection last year but hasn’t been as severe as initially feared in terms of health outcomes.

The example of London illustrates what appears to be the typical dynamic: cases soared above last winter’s levels but appear to have peaked, while the number of patients in hospital and/or on ventilators has been far lower than last January.

It is clear that the vaccines are offering good protection against the risk of hospitalisation and death, and prior infection is also helpful here. However, neither vaccination nor prior infection offer much, if any, protection from infection with Omicron.

Three reasons why Omicron is different

We knew last year that Omicron was different to previous Covid-19 variants. But we now know more about how those differences have resulted in both the faster spread but also the less severe health impacts.

- Firstly, scientists identified very quickly last year that Omicron contained different mutations in spike proteins compared to earlier variants. This enabled it to bypass antibody immunity, leading to greater numbers of people becoming re-infected, or infected or even if they are fully vaccinated. But what we can see now, given the reduced rates of severe illness, is that T-cells – the deeper layers of the immune system – are working well in fighting the virus. That has meant significantly fewer people are severely ill, and has reduced the overall impact on health systems by at least half.

- Secondly, we now know that the specific types of human body cells Omicron is good at infecting is different from previous variants. In effect, Omicron thrives in the upper airways, rather than the lungs. This makes it fundamentally less severe and results in fewer infected people needing hospital treatment, especially mechanical ventilation. We estimate this difference has reduced impact on health systems by around a quarter.

- The third difference – its speed of transmission – is perhaps the most surprising. When Omicron cases were first growing very rapidly in South Africa or in London, researchers assumed that it must be doing so because each infected person was going on to infect many others, as measured by the ‘R number’. When viruses have high R numbers, they invariably only stop spreading once a large proportion of the population has caught the virus, and this threatened to overwhelm hospital systems by sheer volumes of infections. Indeed, this is precisely why the world went into lockdowns in previous waves. However, it now appears that Omicron infections are faster. Multiple lines of evidence (whether Norwegian super-spreading events or South Korean contact tracing studies) point to Omicron infections taking much less time between someone getting exposed to it and then going on to infect others. This means that the peak of the wave, and the total number of people catching Omicron, is turning out significantly lower than previously feared. This has also reduced the total strain on health systems by at least half.

However, Omicron’s strain on healthcare systems has been serious in many countries, and people who have no prior immunity can still be at risk of severe illness.

Countries at different stages in Omicron wave

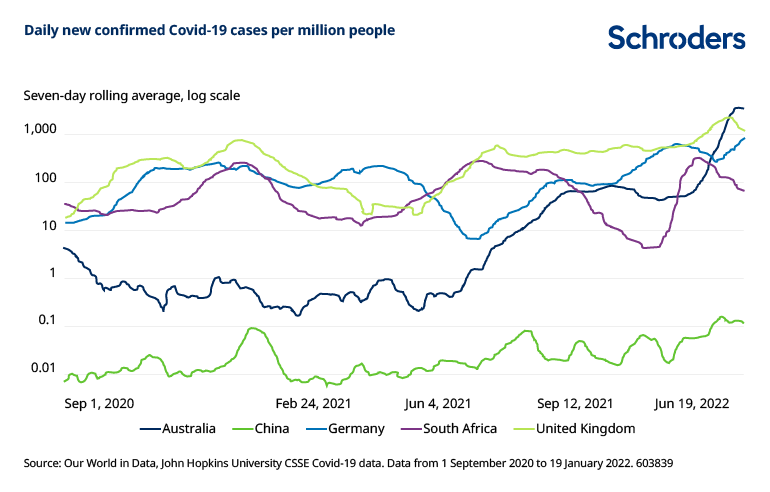

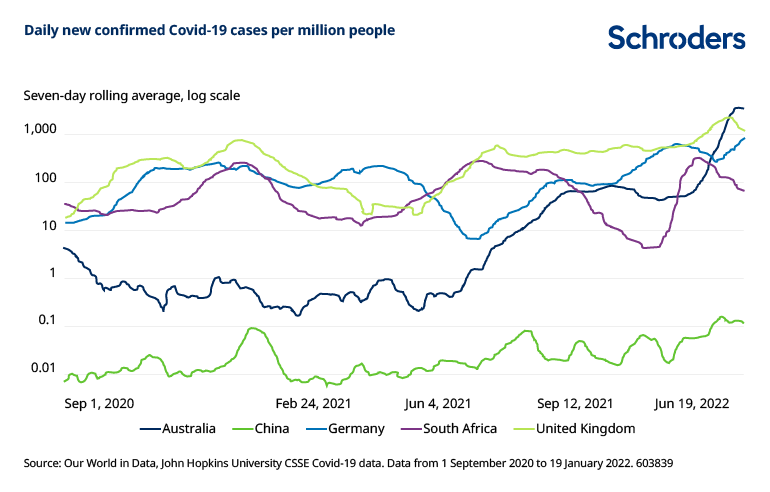

As with the other Covid-19 variants, different countries are experiencing the Omicron wave at slightly different times. Some of the countries that were hit early – such as South Africa, or the UK – are already seeing confirmed cases fall.

Other countries are still experiencing rising cases, such as Germany. However, cases in Germany haven’t risen as high as we might have expected and are showing signs of slowing.

We estimate that many countries where cases are still rising are perhaps only a week or two away from their peak.

Way down will be slower than way up

However, while cases may be starting to plateau or fall, the drop in cases will not be nearly as sharp as the rise. We can see this on the chart above where South Africa’s recent fall in cases is gentler than the preceding rise.

This is because of the interaction between case rates and the population’s behaviour. Some countries were swift to bring in extra restrictions as a result of Omicron. Others did not but populations nevertheless adjusted their behaviour to limit social interactions.

As cases start to drop, governments and populations will become less cautious, restrictions will be lifted and behaviour will gradually normalise. The rate of decline in cases will therefore moderate. So if the rise in cases took two weeks, for example, it may well be one or two months before they fall back to prior levels.

What this means is that although cases may be peaking is some countries, it could still be a few months before we really feel that the Omicron wave is over in terms of pressure on hospitals. We should also remember that hospital occupancy typically peaks two weeks after cases do.

What does this mean for restrictions and economic activity?

As Omicron is moving faster than previous variants, the same may well apply when it comes to unwinding restrictions. Indeed, the UK this week announced that its “plan B” restrictions – which include advice to work from home where possible – will end next week.

The unwinding of restrictions, and voluntary changes in people’s behaviour, will likely take a couple of months once a country has passed its peak of cases. Strain on the healthcare system is likely to be a key factor in governments’ decisions to loosen restrictions.

Clearly, one final crucial point to note is that China is still holding firm to its “zero Covid” strategy. While this has been effective, many other countries which had similar zero Covid policies are now exiting them (for example, Australia, which has experienced sharply rising cases as a result). China’s stance includes strict lockdowns and curtailments of mobility which could continue to put pressure on supply chains and economic activity in 2022.