Rising life expectancy and declining birth rates are resulting in an aging population as well as a widening retirement savings adequacy gap in the ASEAN economies. With the low coverage of mandatory pension schemes and the weakening family-based support for retirement income, the region’s older people are facing serious challenges in maintaining a reasonable standard of living after retirement.

A recent report by Tsao Foundation’s International Longevity Centre Singapore and Mercer and Marsh & McLennan Companies’ Asia Pacific Risk Center delves into this gap and explores potential solutions to enhance the financial security of women in four ASEAN economies—Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand—and in Hong Kong.

A recent report by Tsao Foundation’s International Longevity Centre Singapore and Mercer and Marsh & McLennan Companies’ Asia Pacific Risk Center delves into this gap and explores potential solutions to enhance the financial security of women in four ASEAN economies—Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand—and in Hong Kong.

With more than half (about 60 percent) of the world’s total population of older persons aged 60 years and over,1 the Asia-Pacific region is poised to become one of the oldest regions in the world, with an estimated 1.3 billion older persons by 2050.

There is also growing recognition of the female face of population ageing. In Asia-Pacific, more than half of all older persons aged 60 years and over are women. Ensuring the financial security of these older women will be one of the major social and economic challenges for the Asia-Pacific region. As Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, UN Under-Secretary General and Executive Director, UN Women underlined, “If not addressed, the feminization of aging has the potential to become one of the biggest challenges to gender equality of this century.

Since women live longer than men, older women outnumber older men in all the seven countries, particularly in the older age groups of 80 years and over.

For older women in the seven countries, employment is not a viable route towards financial security. Fewer older women work compared to older men: in 2015, labour force participation of older women over 65 years was highest in Indonesia (28.7%) and Philippines (27.7%). In part, the lower levels of labour force participation could be due to lower levels of education, a reflection of gender inequalities in access to education earlier in women’s lives.

However, a major factor is women’s greater involvement in caregiving and family responsibilities. Caregiving is not confined to older cohorts of women, but impacts upon women of all ages. Women’s domestic responsibilities are the primary reason for the persistence of the gender gap in labour force participation across all age groups in all the seven countries. In Myanmar, for example, almost half (48%) of women aged 15 years and over were outside the labour force and 64% of these women cited housework and family responsibilities as the main reason for not working.

However, a major factor is women’s greater involvement in caregiving and family responsibilities. Caregiving is not confined to older cohorts of women, but impacts upon women of all ages. Women’s domestic responsibilities are the primary reason for the persistence of the gender gap in labour force participation across all age groups in all the seven countries. In Myanmar, for example, almost half (48%) of women aged 15 years and over were outside the labour force and 64% of these women cited housework and family responsibilities as the main reason for not working.

With family support declining, the need for alternative source of income becomes even more urgent. It is doubtful that income from employment can offset the loss of income from family. Education levels have been steadily rising in all seven countries, which have either achieved or are near gender parity in education, but the gender gap in labour force participation rates remains.

Increasing labour force participation rates would entail a change in the distribution of care work. It is estimated that a decrease in unpaid care work would result in a 10% increase in labour force participation.9 Yet, not only does unpaid care remain a female responsibility, but as societies across Asia are rapidly ageing, the increased pressures for caring for the ageing population will only further the need for caregiving.

The main emphasis of policy should be on addressing these competing trends:

1) Changing the conversation around care: In some of the developing ASEAN countries, the focus should start with young girls and ensuring they remain in school and do not drop out to take care of younger siblings. For women of working age, the key factor will be to ensure they enter and most importantly, remain in the workforce. This would involve a range of measures from the provision of childcare, but critically, to changing the mindset around caregiving responsibilities.

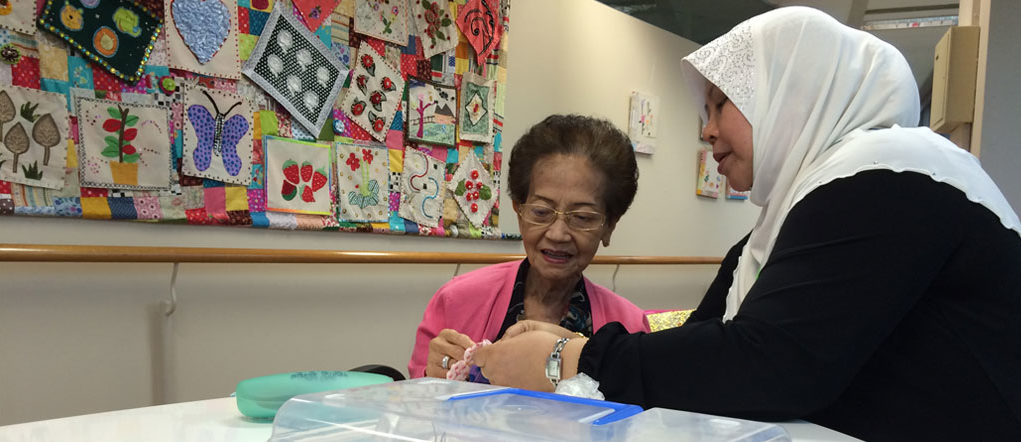

2) Bridging the gap between the ability of families to provide support and actual support provided: Solutions include strengthening community ties, and expanding the scope of non-family support systems such as non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

3) Expanding the reach of social pensions: The role of social protection and in particular, social pensions needs to be explored further.