Companies lagging behind on decarbonisation will be in for an unwelcome cost surprise.

Climate leaders – those that decarbonise their businesses faster than others – will have a rising cost advantage over competitors in the decade ahead.

Unsustainably low carbon prices and offset prices have led to corporate complacency over the cost of carbon emissions.

This is set to reverse and will represent an unwelcome cost surprise for unprepared companies.

Carbon prices are rising

Carbon pricing puts a cost on greenhouse gas emissions. Typically such schemes enable the trading of CO2 emissions allowances. The number of allowances available is gradually reduced over time so that the cost of an allowance rises and emissions fall as businesses are incentivised to invest to reduce their emissions.

Companies with lower emissions need to buy fewer allowances, putting them at a competitive advantage in cost terms.

The majority of academic research and modelling thinks a carbon price of at least €100/tonne (t) is needed to decarbonise the global economy and tackle climate change.

Low carbon prices, or the complete absence of a price on carbon emissions in some geographies, has incentivised a certain type of behaviour and production. This will change.

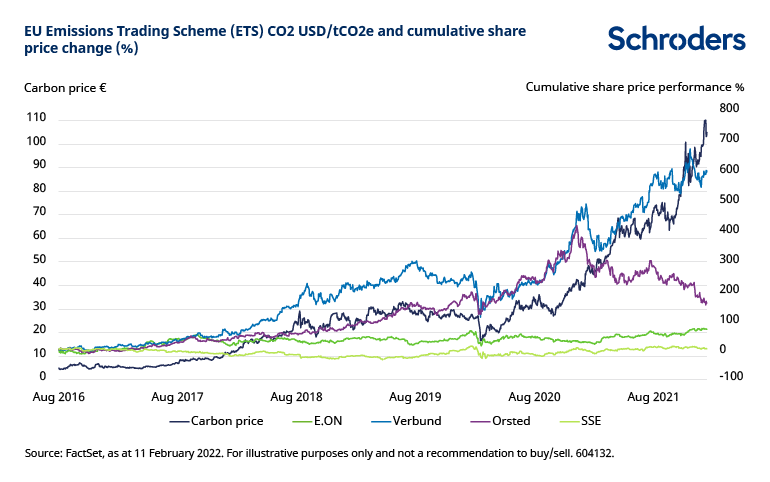

We have already seen a huge impact in recent years from the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), where the price of carbon rose earlier this year to around €100/t (currently around €80/t). This has benefitted low carbon producers.

For example, the chart below shows the share price outperformance of low emission European power generators like Verbund and Orsted versus competitors as carbon prices have soared.

Their profits have risen relative to higher emitters because they have much lower carbon bills to pay. This increases profitability as the price of electricity overall factors in the higher cost of carbon.

By contrast, the utilities suffering today are the ones that were lulled into a false sense of security by a decade of carbon prices at €5/t. That low price led some to conclude they did not need to meaningfully change their business.

Carbon pricing is becoming more widespread

Carbon prices, or similar programmes, are becoming more widespread. The EU ETS is a sign of things to come, with China, Canada, and parts of the US all developing carbon pricing markets modelled on the EU system. Other countries are introducing carbon taxes or levies designed to have a similar effect.

Even within the EU, carbon pricing is poised to expand. The EU carbon pricing scheme has been successful so far in its aims, cutting emissions by about 43% in the industries covered (power and heat generation and energy-intensive industrial installations).

However, more needs to be done to reach the EU’s target to be climate neutral by 2050. The EU has already released plans to expand its ETS across a variety of different industries, including shipping, road transport and buildings.

Carbon offsets to follow path of carbon prices

Meanwhile, some companies are making headlines with their net zero climate plans but many of these are based on widespread use of offsets. Carbon offsets come in many forms; a popular option is investment in reforestation projects.

These offsets are currently cheaper than investing in low emission technology for many industries, leading corporate management teams to conclude that they can rely on offsets instead of investing in low carbon production or technology.

This is an illusion. The price of these offsets, at $5-10/t, is unsustainably low. These companies will be forced to pay much higher prices in future to meet their climate commitments, or walk away from their targets.

Why will offset prices rise?

To understand why the prices of carbon removal offsets will rise, we need to consider the big picture. All countries and participants who signed up to the 2015 Paris climate change agreement have committed to work together to meet the goal of limiting global warming to 2C or below, compared to pre-industrial levels.

It is well established that there simply isn’t enough available land to meet a significant part of global emissions reductions through reforestation. That’s especially the case at a time when the global population is growing and there is rising pressure on agricultural productivity from climate change itself.

For example, Oxfam International estimate that using offsets alone to achieve net zero in the corporate sector would require a land area five times the size of India and larger than all the farmland in the world today. The charity also calculated that the net zero commitments of just four large European energy companies would require the reforestation of land more than twice the size of the UK by 2050.

This scale of land use change, at a time of pressure on crop yields from climate change, is a recipe for soaring food prices.

How far could offset prices rise?

As the demand for reforestation (and other) offsets increases, and the early supply of available land is used up, we can expect prices to rise substantially as competition for land with other uses steps up.

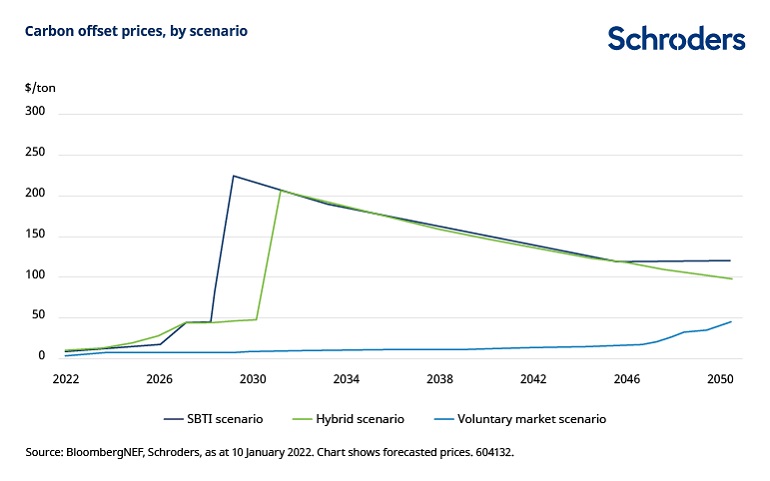

Bloomberg New Energy Finance recently looked at this topic in an excellent research paper (Long-Term Carbon Offsets Outlook 2022: Boom or Bust? 10 January 2022). This examined scenarios for the offset market that factor in forthcoming regulations to standardise the market.

The paper concluded that the price of offsets could increase to $47/t in 2027, and to over $200/t in 2029.

This is in a Science Based Targets scenario (SBTI) in which regulations are tightened so that only actual carbon removal offsets are allowed (i.e. no avoided emissions offsets and no avoided deforestation pledges). This means demand will quickly outstrip supply from corporate net zero plans.

The voluntary market scenario assumes the offset market remains similar to today, and allows offsets that avoid future emissions rather than actually removing them. This leads to excess supply, keeping offset prices low. While it is the situation today, avoided emission offsets are coming under greater criticism and scrutiny. We do not expect their continued use in the corporate sector to be seen as good practice for long.

The hybrid scenario looks at a gradual evolution of the offset market, from the voluntary market today to the SBTi scenario.

Higher offset prices could put big dent in profitability

Let’s take a look at how such a scenario would affect a company using offsets to meet a net zero commitment.

For example, a European airline has pledged to be net zero today by purchasing offsets to account for the entire emissions of running their fleet of aeroplanes from 2020 onwards. Customers are not asked to pay; the company buys these offsets.

In 2019, before the pandemic affected passenger volumes, the airline’s annual emissions were 8.3 million tonnes of CO2. At $5/t CO2, the cost of offsetting these emissions was something in the region of $40 million.

To relate this cost to profits, we again need to look back at pre-pandemic times. In the five years prior to the Covid disruption, this company generated an average of $700 million a year. Therefore, about 6% of underlying profits are spent to take the company to “net zero”.

It doesn’t take a degree in mathematics to work out that at the EU ETS price of €100/t, or Bloomberg NEF’s squeeze scenario for offset prices of over $200/t, there would be no post carbon profits.

Low carbon leaders will have a cost advantage

Offset prices are seductively, unsustainably low. They can’t be justified, and won’t stay there.

It is just common sense that as the world increasingly puts a price on carbon emissions, the value of a tree that takes 50 years to mature and stores one tonne of carbon, on average, will be worth much more than $5. Some companies are therefore making a big mistake by committing too much of their climate efforts to offsets.

Whether companies face costs through an official scheme like the EU ETS, a government tax on carbon, or the rising price of offsets they have committed to buy in their net zero sustainability pledges, one thing is clear.

Those companies that really reduce absolute emissions now will be much better placed as the true cost of emissions come through.